The Big Lie

We live in a world where all information must be scrutinized very carefully. Unfortunately, not everyone has access to all the information necessary to make evaluative studies and comparisons. There is a market to sell anything and everything (see my previous articles on grounding and sugar as examples). There are particularly few sources of unbiased truth on the matter of nutrition. My blog has been aiming to be one of these sources for over a decade.

This time I am biting into a huge toxic subject: plant antioxidants.

The subject is toxic because there are many commercial enterprises committed to making and keeping people eating plants and buying plant-based supplements, touting their various nutrient benefits, among others, as sources of antioxidants. In this article, my goal is to show you that for the most part, with only a couple of exceptions, there is no such thing as a “plant antioxidant” that works in humans as an antioxidant. Plants do not provide antioxidants for humans. What they provide are chemicals that irritate us into releasing our own endogenously created antioxidants. There are only two exceptions to this: vitamins C and E. All other so-called plant-antioxidants are irritants that make us release our own endogenously made antioxidants.

Put it in another way, plant chemicals act as hormetic forces and initiate adaptive response by irritation, aka hormesis. Hormesis refers to a biological phenomenon where exposure to a low dose of a stressor or toxin induces a beneficial adaptive response, whereas a higher dose can be detrimental. It’s often described as “that which does not kill us makes us stronger“.

This paper will debunk the “plants as beneficial sources of antioxidants” theory. I will explain what an antioxidant is, how it is used by our body, how it is endogenously created by us, and importantly to the subject of this paper, what plant antioxidants are and how our body uses them—if it does at all.

So buckle your seatbelt because this is going to be a bumpy ride.

Human Antioxidants

Understanding Free Radicals, Non-Radicals, and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

Elements that cause oxidative damage by ROS, oxygen-containing reactive molecules, come in two flavors: free radicals and non-radicals.

Free Radicals

A free radical is a molecule or atom with an unpaired electron, making it highly reactive. An example for a free radical is hydroxyl radical (HO·).

Non-Radicals

A non-radical, is an element that can lead to similar reactions to free radicals without having unpaired electrons, so without being “free radical”. An example for a non-radical is hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂).

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

ROS are the collection of oxygen-containing reactive molecules, such as free radicals and non-radicals. ROS are highly reactive and they damage biological molecules. Free radicals and non-radicals are naturally generated during cellular processes such as mitochondrial energy production and immune responses. ROS is a natural phenomenon that our body deals with every day (De Palma & Clementi, 2014).

There are also beneficial processes associated with generating ROS. Our immune system uses ROS to defend our body. So not all ROS are bad. But having too much of a good thing may be bad. And not just having too much ROS but surprisingly having too much antioxidant can also be a bad thing. The goal is not to have too much or too little but to minimize the destructive actions of ROS but still have enough available to use as a weapon, when needed.

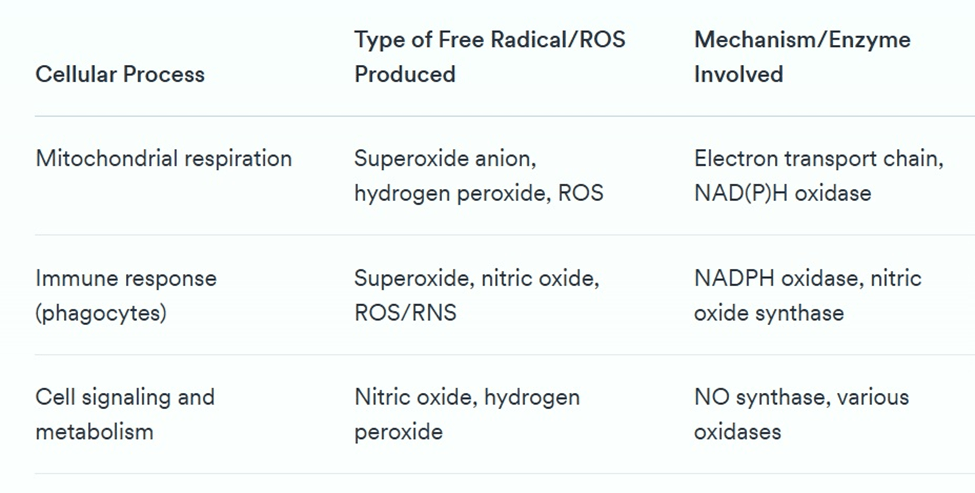

Main Sources of ROS and Free Electrons in Cells

Table 1. Samples of ROS and free electrons in some cellular processes.

For further study on free radicals, read (Bak et al., 2025; Sadiq, 2021; Sas et al., 2007).

As we can see in Table 1, ROS play vital roles in signaling and defense. Excessive amounts of ROS can damage DNA, proteins, and lipids—a condition called oxidative stress. To maintain balance, the body produces its own antioxidants, including enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase, and catalase, along with small molecules like glutathione, uric acid, and coenzyme Q10. See Table 2 for more details.

These internal antioxidants act as protective agents, keeping cellular functions stable, preventing inflammation, premature aging, and degenerative diseases. Our body’s own (self-created, endogenous) antioxidants are finely regulated to be the right amount in response to fluctuating ROS levels. Understanding how these internal systems work, especially how they are supported or disrupted by endogenous antioxidants, helps us better interpret the real impact of diet and lifestyle.

Note that I wrote “self-created” endogenous antioxidants, meaning, the antioxidants we create via our metabolic processes at a molecular level from the foods we eat, as opposed to eating what are labeled as already formed antioxidants, such as plants or supplements. An example of this is glutathione, the main human antioxidant we produce. Glutathione is made in the body through a two-step enzymatic process that combines the amino acids cysteine, glutamic acid, and glycine—these are the most common amino acids found in most every food we eat and are also generated by our body, so they are nonessential amino acids, which you generate even if you eat nothing. Nonessential means it is so important that our body makes it all the time so it need not depend on receiving it from food. A contrasting example is phytates (phytic acid), available only in certain plants, a purported plant antioxidant, something non-essential that we can only get from our food.

How Are Human Endogenous Antioxidants Made?

Human antioxidants are synthesized in our body through complex biochemical pathways involving amino acids, vitamins, and minerals as building blocks and cofactors. For example, glutathione, the most abundant intracellular antioxidant, is made in our liver. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is a protein enzyme produced from specific genes and requires trace minerals such as zinc, copper, or manganese, depending on the kind of SOD, to function properly.

Other human antioxidants like catalase (which breaks down hydrogen peroxide) are also enzyme-based and require iron as a cofactor. Coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone), crucial in both energy production and antioxidant defense in mitochondria, is synthesized through the mevalonate pathway (which also produces cholesterol) and from cholesterol, it creates steroid hormones, such as testosterone. These antioxidant systems are tightly regulated by the body based on demand, and they rely on sufficient dietary protein, minerals, and metabolic health for optimal function.

The Making of a Human Antioxidant

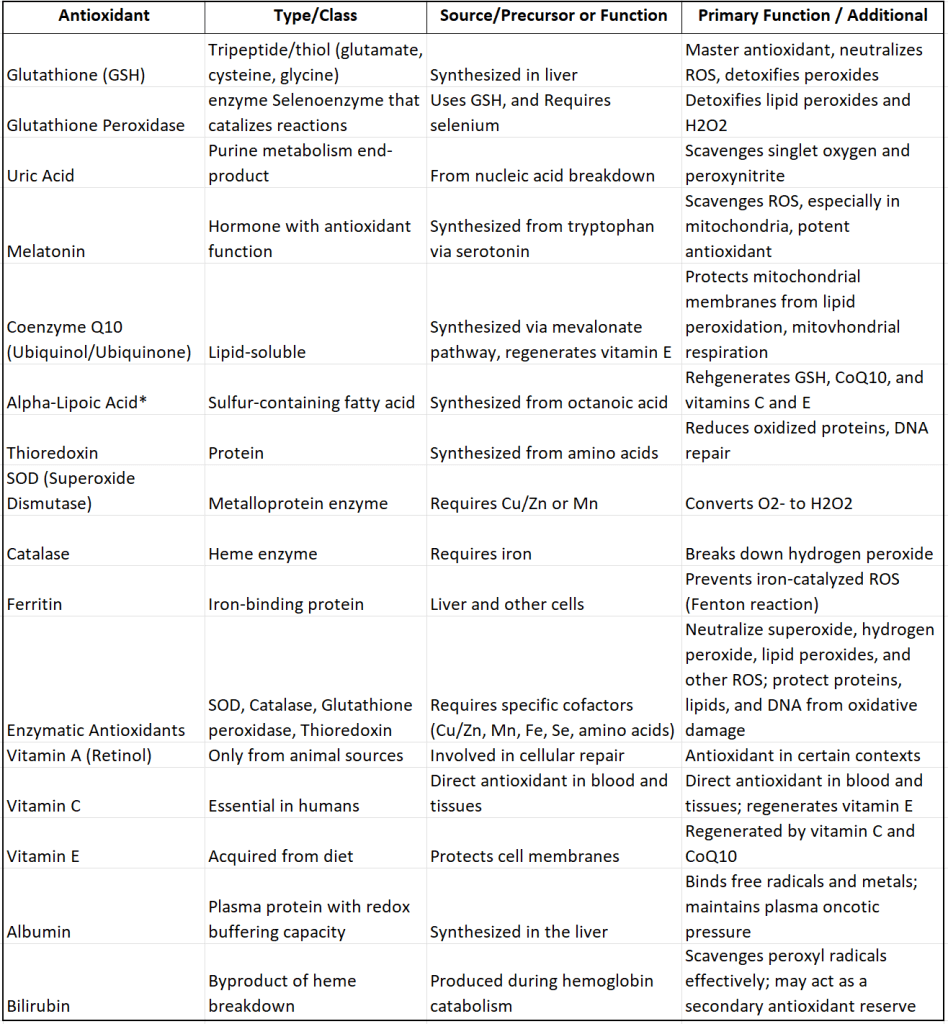

Table 2 lists most of the chemicals we humans use as “raw material” to create our own enzymes needed to manufacture antioxidants endogenously and table 4 lists the antioxidants thus created. None of what you see in these two tables is exogenous “plant-derived” antioxidant and no part of these enzymes and antioxidants needs the consumption of plants to be created or used.

Endogenous Enzymes and Substances Involved in Antioxidant Creation

Table 2. Human-Made (Endogenous) Antioxidants

In Table 2 you can see all the enzymes, cofactors, substrates, and precursor molecules essential for endogenous production of human antioxidants.

Next to Alpha-Lipoic Acid (ALA) in Table 2, I placed a star because I know that some of you are thinking: “wait a minute, we supplement ALA because we are told it is essential to be supplemented”. But this isn’t necessarily true! We are capable of making our own ALA endogenously! ALA is a sulfur-containing compound essential for mitochondrial function. ALA is synthesized in the mitochondria from octanoic acid and cysteine through a series of enzymatic reactions. This process is crucial for its role as a cofactor in mitochondrial enzyme complexes and for its antioxidant properties. (Mayr et al., 2014). And if we can make enough of it, we need not eat/supplement it. In our youth we are capable of making sufficient amounts. Only in the elderly might there be a decrease in production where supplementing ALA may provide benefits.

Over- or under- production of antioxidants can disrupt redox signaling or increase oxidative stress. The important process of antioxidant regeneration is to convert oxidized antioxidants back into their active, reduced form of antioxidants—see discussion here. This is one reason why you don’t actually want to supplement antioxidants; you may just create too much antioxidant, interfering with the antioxidant regeneration system as well as potentially destroying some of your immune system strength by reducing the available oxygen too much! Too much of a good thing can be bad for your health!

What is Oxidative Stress?

Oxidative stress refers to a biochemical state in which the body’s production of ROS exceeds the body’s ability to neutralize them with antioxidants. ROS are highly reactive molecules that contain oxygen and are generated naturally during essential processes like energy production in mitochondria, immune defense (e.g., via macrophages), and detoxification. ROS are utilized by the immune system to combat pathogens. Phagocytic immune cells, like neutrophils and macrophages, produce ROS to damage and kill invading microbes. This process, known as the oxidative burst, which you can think of as a “grenade” made of oxygen, is a crucial part of the body’s defense mechanism against infections. Recall that oxygen can be a very dangerous gas.

One of the biggest extinction events happened on earth a long time ago when all organic life was anaerobic and there was hardly any oxygen in the atmosphere. As oxygen levels increased over millions of years, a large portion of anaerobic life forms became extinct and new aerobic life forms evolved. But some anaerobic life forms are still with us. Inside our body, many bacteria, including those in the gut, are anaerobic and thrive in oxygen-poor environments. Most cancer types are anaerobic as well. Using oxygen selectively, our immune system can control the existence and location of these microbes as well as cancer cells.

While low levels of ROS are important for signaling and defense, an excess can damage proteins, lipids, DNA, and cellular membranes. As we have seen, the human body prevents this damage using a sophisticated system of endogenous antioxidants, including glutathione, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and others, which works continuously to restore balance and prevent cellular injury (see the list in table 2). Thus, managing ROS is not about eliminating them entirely but maintaining a balanced redox state (Schafer & Buettner, 2001) where their benefits can be harnessed without triggering harm.

The most typical functions that generate oxidative stress include mitochondrial respiration (especially during high ATP demand), immune activation (e.g., inflammation or infection), detoxification of drugs or environmental toxins, and intense physical exercise. Other common contributors include poor glycemic control, excessive iron or copper, chronic stress, UV radiation, and exposure to cigarette smoke or pollutants. In these scenarios, the body produces ROS as part of its normal physiology or in response to challenges—but when antioxidant capacity is overwhelmed or compromised, oxidative stress ensues. This imbalance is implicated in aging and numerous diseases, such as neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and cancer.

What Are Plant Antioxidants

Unlike human-made (endogenous) antioxidants, most plant antioxidants are not directly used by our bodies as antioxidant enzymes or compounds, so they aren’t true antioxidants. Rather, most plant-made antioxidants act through a hormetic effect — meaning they mildly stress or irritate human cells, triggering the body’s own antioxidant defenses to become active. This effect is mediated largely through the Nrf2 pathway, which upregulates the production of human antioxidant enzymes like glutathione peroxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase in response to small, manageable doses of oxidative stress from the plant compounds. In other words: plant antioxidants don’t add to human endogenous antioxidants; they merely initiate their actions. Exogenous antioxidants derived from plant-based sources, such as polyphenols and vitamins, upregulate endogenous antioxidant enzymes (see here).

Many plant compounds that are marketed as antioxidants — such as polyphenols, flavonoids, tannins, and terpenes — are actually pro-oxidants. Pro-oxidants are substances that promote oxidative stress within the body, either by generating ROS or by inhibiting the body’s natural antioxidant defenses (see here). They create low-level ROS or disrupt cellular redox homeostasis just enough to activate endogenous antioxidant genes. This response is protective not because the plant compound itself neutralizes ROS, but because it forces our body to do so by enhancing its own defense systems. While this can be beneficial in moderation, it is critical to understand that plant antioxidants are not replacements for endogenous antioxidants.

Common Plant Compounds Labeled as Antioxidants and Their Actions

Note the colored terms in Table 3. I will explain each so you can see how plant antioxidants create chaos, which then the endogenous antioxidants (generated without any plant-based input) rush to clear up.

Table 3. Plant chemicals labeled as antioxidants

The Terms shown in red in Table 3 explained

Hormetic

Beneficial in small doses by triggering adaptive stress responses. The following is a list of hormetic treatments:

- Vaccines: Introduce a controlled immune challenge, prompting adaptive immune memory without causing disease.

- Sauna: Heat stress induces heat shock proteins and improves cardiovascular and cellular resilience.

- Ice plunge: Cold stress activates thermogenesis, norepinephrine release, and mitochondrial adaptation.

- Fasting: Nutrient deprivation activates autophagy, mitochondrial efficiency, and stress resistance pathways.

- Exercise: Mechanical and metabolic stress stimulates muscle repair, mitochondrial biogenesis, and antioxidant defenses.

Pro-oxidant

Promotes oxidation, increasing free radicals, so it increases oxidative damage in order to stimulate the human body to release endogenous antioxidants, made without plant antioxidants.

ROS generator

Produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are unstable oxygen-containing molecules.

Mild mitochondrial disruption

Slight interference with mitochondrial function, triggering adaptation. In other words: it hurts a bit in order to activate protective response.

Electrophilic stressor

A reactive compound that targets electron-rich (nucleophilic) sites in cells, often generating ROS and activating defense pathways like Nrf2.ROS generation via redox cycling or mitochondrial stress.

Mitochondrial stressor, inhibiting complex I and III

Disrupts energy production by blocking key enzymes in the mitochondrial electron transport chain.

Oxidative stress

Imbalance between ROS and the body’s ability to detoxify them, leading to cell damage.As you can see, plants really aren’t providing antioxidants.

Why Plant Antioxidants Don’t Work as Antioxidants for Humans

Plants have cells with cellulose as membrane while animal cell have lipid membranes. The biology of plants and animals is very different, so what works in plants in a certain way, such as providing a biological function like antioxidants do, is very different from how it works in animals.

Human Endogenous Antioxidants

These are endogenous—made within our body independent of what we eat—and function directly without any indirect actions like plant antioxidants do. Human endogenous antioxidants work to neutralize ROS and repair oxidative damage without the need to induce hormetic stress or other irritants.

What About Vitamins C, A, and E? Plant Antioxidants.

Vitamin C is biosynthesized from glucose in most animals—but crucially, not in humans. In case of humans, when vitamin C is consumed with sugar (fruits and vegetables), there is a competition between the uptake of glucose and of vitamin C. Glucose can be removed by the GLUT (insulin transport) or the SLGT (facilitated sodium transport SVCT1/SVCT2 Na⁺-coupled) systems from the blood. Vitamin C uses the GLUT(1/3/4) receptors, but glucose will win the competition for GLUT receptors—the insulin driven receptor—because it is much more dangerous to have high blood sugar levels for the human body than to have high vitamin C levels in the blood. So vitamin C, when consumed with high carbs plants, will be excreted in the urine rather than absorbed.

The competition:

- Glucose and DHA (the oxidized from for vitamin C, Dehydroascorbic acid and not Docosahexaenoic acid (also DHA by some weird acronym selection) compete for the same GLUT transporters).

- High blood glucose (or lots of sugar in the gut) outcompetes DHA, reducing how much vitamin C is absorbed.

This is often referred to as the “glucose-ascorbate antagonism.” Furthermore, excess vitamin C can be metabolized into oxalate, which may bind to calcium to form calcium oxalate, the primary component of most kidney stones. Unlike other plant “antioxidants”, vitamin C is a direct, fast-acting exogenous antioxidant in humans. It neutralizes ROS (like superoxide and hydroxyl radicals) by donating electrons directly in blood and tissues, without needing to trigger a hormetic stress pathway first.

Vitamins A and E are highly specialized into very specific roles. Vitamin A in plants is beta carotene (carotenoid) that is not useable “as is”. It first needs conversion to retinol to be able to work in a human body as an antioxidant. Vitamin A (retinol & carotenoids) – fat-soluble, mainly quenches singlet oxygen and lipid radicals, especially in low-oxygen environments like membranes and the eye.

Vitamin E – fat-soluble, primarily protects lipid membranes from peroxidation by neutralizing lipid radicals. High-dose vitamin E supplementation is linked to an increased risk of hemorrhagic (bleeding) stroke and, in some cases, may increase cancer risk (Maggio et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2019).

Eating too many plant products causes autoimmune diseases as well. These compounds keep on activating our natural immune and antioxidant systems that are meant to deal with real danger whenever it may arise, which leads to an “over-activation-syndrome”, aka autoimmune disease.

To review: most plant compounds commonly labeled as antioxidants — such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and other phytochemicals — do not directly act as antioxidants in the human body in the way many people assume (i.e., by donating electrons to neutralize free radicals). Instead, their primary mechanism of action is hormetic: they create mild stress by increasing ROS a little, which in turn activates the body’s endogenous antioxidant defense systems, especially the Nrf2 pathway. This is a great example of adaptive evolution in humans.

Here’s how it works in detail:

- Mild oxidative stress from plant compounds activates Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2), a transcription factor.

- Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus and upregulates genes that code for endogenous antioxidants, such as:

- Glutathione peroxidase

- Superoxide dismutase (SOD)

- Catalase

- Heme oxygenase-1

The net result: an increase in the release of the already existing antioxidants rather than a donation of antioxidants from the plant compounds themselves. This hormetic effect explains why dose and context are so important. In small amounts, these plant compounds can be beneficial via this adaptive response, but in large amounts—or in sensitive populations—they can be toxic or pro-oxidant.

“Plant antioxidants don’t give you antioxidants — they signal your body to make its own.”

Why This Matters

- This is not true antioxidation, it’s a controlled oxidative stress that the body learns to deal with over time.

- This pathway is dose-dependent and biphasic:

- Low doses = beneficial hormesis

- High doses = toxic oxidative stress (can damage mitochondria, DNA, proteins)

- People with compromised redox balance, like those with mitochondrial disorders, chronic fatigue syndrome, or severe nutrient deficiencies may not tolerate even mild oxidative trigger that plants create in the process of antioxidation.

Antinutrients

The antioxidants we think of when we think of plant antioxidants are actually antinutrients. Phytate, oxalate, cyanide, saponins, and tannins are such chemicals. They primarily interfere with our nutrient absorption or metabolism. For example:

- Phytate binds to minerals like zinc, iron, and calcium, reducing bioavailability.

- Oxalate forms insoluble salts with calcium and contributes to kidney stones.

- Cyanide from certain plant foods is outright toxic in excess.

- Saponins and tannins can disrupt cell membranes or impair protein digestion.

These are not health-enhancing compounds; they are plant defense chemicals, and while a small hormetic effect may exist in some cases, the idea that they “add antioxidants” to the human body is a myth rooted in misunderstanding of redox biology.

The Complete Human Antioxidant Picture

| Class | Source | Mechanism of Action | Function in Humans |

| Thiol Antioxidants | Endogenous | Detoxifies ROS, maintains redox balance | Master antioxidant (GSH); supports detoxification |

| Enzymatic Antioxidants | Endogenous | Neutralizes superoxide, H2O2, and other ROS | First-line enzymatic defense system |

| Melatonin | Endogenous | Protects mitochondria, modulates sleep and circadian rhythm | Mitochondrial protection, antioxidant signaling |

| Uric Acid | Endogenous (purine metabolism) | Antioxidant in plasma, pro-oxidant in excess | Plasma antioxidant reserve |

| Coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinol) | Endogenous (also dietary) | Mitochondrial antioxidant, regenerates Vitamin E | Supports mitochondrial respiration |

| Lipoic Acid | Endogenous (also dietary) | Dual-soluble antioxidant, regenerates GSH, C, E | Bridges mitochondrial & cytoplasmic redox systems |

| Vitamin A (Retinol) | Dietary (animal sources only) | Supports cell repair, mild antioxidant | Retinoid signaling & repair |

| Vitamin C (Ascorbate) | Essential dietary (humans can’t synthesize) | Direct antioxidant in blood/tissues | Primary water-soluble antioxidant |

| Vitamin E (Tocopherol) | Dietary (regenerated by C & CoQ10) | Protects membranes, breaks lipid peroxidation chain | Main lipid-soluble antioxidant |

| Albumin | Endogenous (liver-produced) | Redox buffer, binds free radicals and metals | Plasma redox homeostasis |

| Bilirubin | Endogenous (heme breakdown) | Scavenges peroxyl radicals effectively | Detox byproduct with antioxidant role |

| Polyphenols | Plant-based (fruits, tea, cocoa) | Pro-oxidant/hormetic in humans, activates NRF2, induces phase II enzymes | Indirect antioxidant via stress response |

| Phenolic Acids | Plant-based (coffee, berries) | Scavenge ROS, activate defense pathways | Modulate inflammation, gut health |

| Flavonoids | Plant-based (tea, citrus, onions) | Hormetic action via NRF2, anti-inflammatory | Trigger protective gene expression |

Table 4. Key Endogenous and Semi-Endogenous Antioxidants: Classes, Examples, and Functions

Table 4 is a comprehensive summary of the major antioxidant systems in the human body, where they come from and how we use them. They include:

- Endogenously produced antioxidants (e.g., glutathione, uric acid, enzymatic antioxidants).

- Nutrient-derived antioxidants that humans must consume (e.g., vitamins A, C, E).

- Physiological byproducts with antioxidant capacity (e.g., bilirubin, albumin).

- Borderline cases like CoQ10 and lipoic acid, which are synthesized internally but also available from diet or supplements.

The table contrasts human (endogenous) antioxidant systems with plant-derived compounds, to clarify the differences between how our biology manages redox balance vs. how plant polyphenols act as pro-oxidants or hormetics. It highlights the integrated roles of enzymatic systems, redox buffering proteins, mitochondrial antioxidants, and essential vitamins. It emphasizes how our endogenous systems regenerate each other (e.g., Vitamin C regenerating Vitamin E, CoQ10, and glutathione), which is not how plant polyphenols function.

Sources:

Bak, S., Kim, E.-K., Lim, H.-J., Won, Y.-S., Park, E. H., Park, S.-I., Lee, S., & Chandimali, N. (2025). Free radicals and their impact on health and antioxidant defenses: a review. Cell Death Discovery, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-024-02278-8

De Palma, C., & Clementi, E. (2014). Reactive Species and Mechanisms of Cell Injury. In L. M. McManus & R. N. Mitchell (Eds.), Pathobiology of Human Disease (pp. 88-96). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386456-7.01405-2

Maggio, E., Bocchini, V. P., Carnevale, R., Pignatelli, P., Violi, F., & Loffredo, L. (2023). Vitamin E supplementation (alone or with other antioxidants) and stroke: a meta-analysis. Nutrition Reviews, 82(8), 1069-1078. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuad114

Mayr, J. A., Feichtinger, R. G., Tort, F., Ribes, A., & Sperl, W. (2014). Lipoic acid biosynthesis defects. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, 37(4), 553-563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10545-014-9705-8

Sadiq, I. Z. (2021). Free radicals and oxidative stress: signaling mechanisms, redox basis for human diseases, and cell cycle regulation. Current molecular medicine. https://doi.org/10.2174/1566524022666211222161637

Sas, K., Robotka, H., Toldi, J., & Vécsei, L. (2007). Mitochondria, metabolic disturbances, oxidative stress and the kynurenine system, with focus on neurodegenerative disorders. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 257(1), 221-239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.033

Schafer, F. Q., & Buettner, G. R. (2001). Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 30(11), 1191-1212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00480-4 Wang, J., Guo, H., Lin, T., Song,

Y., Zhang, H., Wang, B., Zhang, Y., Li, J., Huo, Y., Wang, X., Qin, X., & Xu, X. (2019). A Nested Case–Control Study on Plasma Vitamin E and Risk of Cancer: Evidence of Effect Modification by Selenium. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119(5), 769-781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2018.11.017

Comments are welcomed, as always, and are moderated for appropriateness,

Angela

Pingback: Bean-Eaters’ Tragedy 2025-2030: The New DGA | Clueless Doctors & Scientists

Pingback: How to Prevent Being Floxed | Clueless Doctors & Scientists

Pingback: The Fiber War | Clueless Doctors & Scientists

But what is your conclusion? Do we need plants? Is a small dose beneficial?

For now I stay carnivore.. 🙃

LikeLiked by 1 person

Otto,

This wasn’t a discussion on whether we need to eat plants or not. I simply wanted people to understand that plants do not provide nutrients. So if you are told to eat plants for their “nutrients” then no, you need not eat any plant for their nutrients becuase we can get all nutrients that are in plants from animal products–even vitamin C. So plants are not essential at all.

There is zero need to eat plants, unless for whatever reason animals aren’t available and you are starving. In that case plants become quite useful. And ancestrally that was the reason why plant-eating happened and why grains were “domesticated” and first planted. They provided a steady something to fill the stomach with even if it had minimal nutrition. Plants are tasty, full of carbs, and people love them.

In summary: no, you don’t need any plant but you can have them if you wish but not for their nutritional value… have them for fun if you like them.

Angela

LikeLike

thank you for your extensive reply! I consider plants as backup nutrients.

and for now I don’t need them…

🙃

LikeLiked by 1 person